How Access to Care and Insurance Affects Medical Debt

BySteve Tanner

UpdatedJun 19, 2025

- Lower income Americans are more likely to incur unaffordable medical debt.

- Access to insurance and healthcare is not equal across all races.

- The result is that minority and lower income Americans are less healthy.

Table of Contents

The United States is unusual among developed countries in that employment and income drive access to medical care. Because of this, low-income Americans and those without employer-sponsored health insurance are often less healthy. But employment status isn’t the only issue for minorities – studies show that people of color are more likely to receive worse care than white patients, regardless of their insurance coverage or medical provider.

And in the US, financial well-being and physical health are linked – financial difficulty often creates health problems, and ill health can generate financial difficulties. This cycle contributes to the widening divide between haves and have-nots in the US.

The link between health coverage and financial health

To make the discussion a bit more concrete, let’s consider a young Black student whose family can’t afford to send him to college. A high school education then limits him to jobs that often don’t offer health care benefits, or only offer plans with very high deductibles. The plan he can afford may also lack prescription coverage, and that high deductible discourages him from getting regular checkups or taking certain medications.

Suddenly, he becomes hospitalized for untreated diabetes. Now saddled with medical debt, and missing a week or two of work, he gets behind on payments to credit cards, and his car loan. Now his credit score takes a hit. And that is just the beginning of the physical and financial costs that can often result from of lack of access to health insurance and medical care.

As with the legacy of redlining, business loan bias, and other forms of credit discrimination, limited access to health insurance and medical care may disproportionately affect minorities and may have numerous long-term consequences, as illustrated in our example above. A health condition that is too expensive to address without adequate coverage can easily become a financial hardship. While we can’t possibly solve these deeply ingrained problems, we hope to shed some light on the issue and help people make the best possible choices.

The racial health coverage gap

The racial health coverage gap tracks closely to the racial wealth gap. The good news is that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) significantly increased health insurance coverage among people of color, especially after participating states expanded Medicaid in 2014, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation study. Hispanics decreased their uninsured rate from 32.6 to 19.1 percent between 2010 and 2016, while Black Americans decreased theirs from 19.9 to 10.7 percent during that same period.

But people of color still have much higher uninsured rates than whites, according to the Kaiser study. In 2018, the Black uninsured rate was 1.5 times higher than it was for whites, and the Hispanic uninsured rate was 2.5 times higher. The study also shows that Blacks are more likely than whites to fall into the ACA coverage gap in states that declined to expand Medicaid coverage.

A lot more needs to be done to provide greater access to care and insurance for people of color, but it used to be much worse. New examination of the topic traces the current deficiencies in health care coverage among people of color back to the legacy of slavery.

According to the New York Times’ 1619 Project series, newly freed slaves in the post-Civil War era were denied access to mainstream health services across the South, although they suffered poorer health as a result of malnutrition and inadequate sanitation. In 1945, federal grant money for new hospitals managed by state authorities was routinely allocated away from Black communities, while medical schools excluded Black students. Those are just a few examples of racialized health care inequities, but the list is long.

Today, about 30 million Americans are uninsured and half of them are people of color, according to a 2020 Brookings Institution report. Much of the current racial health coverage gap could be remedied if the 14 states that refused to expand Medicaid were to change course, according to the report’s authors, since they also happen to have the largest minority populations. More than 90 percent of those surveyed for the report who don’t have insurance because their state didn’t expand Medicaid coverage live in the South.

Without adequate coverage, people often can’t afford prescription drugs for chronic illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease; may not discover treatable illnesses until it’s late (such as late-stage cancers); and, if they do seek medical treatment, are more likely to go into debt paying for it.

Despite access, minorities receive inadequate care

Getting insured and accessing medical care is only half the battle for people of color. A 2005 study by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) found that minorities receive lower-quality health care than whites, “even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable.” This means that aside from the obstacles to coverage, just their racial or ethnic characteristics could make them less likely to receive high quality care.

The NAM report has been backed by other studies that reach the same conclusions. One study of 400 hospitals (cited in the link above) found that, compared to similarly situated white patients, black patients are:

Given older, cheaper, and less innovative treatments for heart disease.

Discharged from the hospital following surgery earlier, often before it is typically recommended by physicians.

Less likely to receive a mastectomy or radiation treatment for breast cancer.

More likely to be prescribed antipsychotics for bipolar disorder, despite a lack of effectiveness and having serious long-term side effects.

More likely to have limbs amputated, when other alternatives may be available.

The devastating effects of this gap in the quality of care along racial lines has been well documented, and can be witnessed in the current COVID-19 crisis. After adjusting for age, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Black Americans are contracting COVID-19 at five times the rate of white individuals. Latinos are four times more likely than whites to contract COVID-19. Studies also show a much higher death rate from the disease among minorities.

Achieving equitable health care outcomes among different racial groups isn’t as simple as rooting out racist caregivers, though. In most cases, it’s “implicit bias” rather than overt racism. Doctors typically don’t realize they’re treating minority patients differently, as it’s generally done unconsciously and based on emotional cues. Some medical schools are trying to deal with this before students begin working with patients, with mixed results.

When lack of access to medical care becomes medical debt

When some or all of your health care costs must be paid out-of-pocket, personal health can feel like just another line item on your budget that needs to be prioritized. If you’re short on rent, for instance, you may have little choice but to go without your medications for a few days to make up the difference and avoid eviction. This obviously could create health complications that cost you in the future, but you need to pay rent right now.

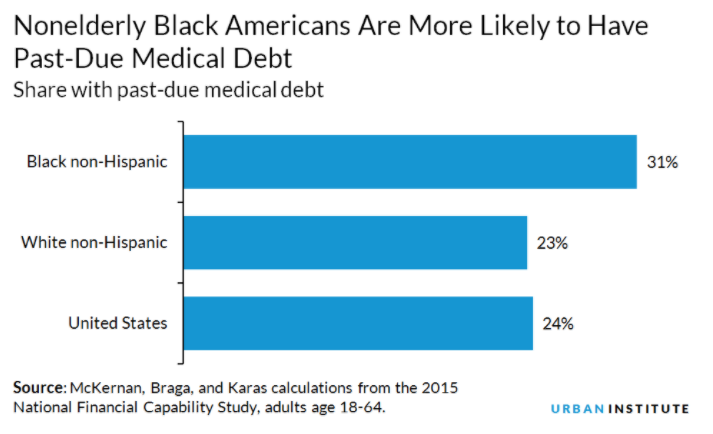

Since health care and personal finance are joined at the hip, it stands to reason that a chronic health condition, serious accident, or medical emergency could easily lead to crippling debt that can’t quickly be paid off. Not surprisingly, this has a disproportionate impact on people of color. Thirty-one percent of nonelderly Black Americans are more likely to have past-due medical debt, compared to 23 percent of whites, according to the Urban Institute.

If you carry past-due medical debt, it will be reflected in your credit report and can lower your credit score. About one-half of all debts in collections that appear on credit reports are for medical bills claimed to be owed to medical providers, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The CFPB estimates that medical debt impacts the credit reports of nearly one-fifth of all consumers being tracked by credit reporting agencies.

This lower credit score can, in turn, keep you from renting an apartment, buying a car or a home, or even getting a job. It may even impact how much you pay in insurance premiums or how high your interest rates are for credit cards. When you’re already struggling to pay down debt related to your health care, these additional stresses can result in a vicious cycle that’s difficult to escape.

Several factors contribute to the disproportionate amount of medical debt held by people of color, including:

Higher uninsured rate. Despite gains from the 2010 implementation of the ACA, 17% of nonelderly Black Americans are uninsured, compared to 12% of nonelderly whites.

Lack of funds to pay for medical emergencies. Wealth inequality has not improved over the past 50 years, which means low-income individuals (disproportionately people of color) are often unable to build emergency funds which can be used to pay unexpected medical expenses.

Higher rates of certain illnesses. Nearly half of all African Americans have some form of cardiovascular disease (compared to one-third of whites), and also are at a higher risk of cancer, infant mortality, and lead poisoning.

Historical and structural discrimination. Employment discrimination, redlining, and other obstacles to health coverage and wealth creation have led to disparate outcomes in health care along racial lines.

Poorer treatment. When minorities receive inadequate care, regardless of coverage or which facilities they use, they’re more likely to need additional interventions later, which of course, cost more money.

Economic factors accounted for 19.4 percent of the medical debt disparity between Black Americans and whites, according to a 2016 study by the American Journal of Public Health. The study also found that income was a more important factor than insurance status, which suggests that African Americans are more likely to have plans with high deductibles and inadequate coverage in general. Health factors explained 22.8 percent of this disparity.

How to protect your health and finances

Overcoming implicit bias at the point of care, expanding coverage, and realizing a more equitable distribution of wealth all require concerted efforts by lawmakers, leaders in the private sector, and the medical community. No solution will be simple, however, here are a few things we can all do to care for our physical and financial health.

Financial literacy

One solution that is within everyone’s reach is to learn more about how finances work in general. The Urban Institute found that nonelderly adults who correctly answered at least four out of five questions on a financial knowledge quiz were 7 percent less likely to have past-due medical debt than those who got one or zero answers correct. This study controlled for health insurance status, income, disability, and other such factors.

Understand your coverage, ask for help if you need it

Paying medical bills is not like paying rent. Given the complicated nature of medical bills, it can be confusing to understand what is actually covered by the insurance provider and how the deductible is applied. Some hospitals and medical facilities provide an estimate of the total out-of-pocket cost, but the process can still be confusing. If you have questions about your medical bills, it’s best to contact the provider as soon as possible. You may be able to work out a payment plan, but you need to be proactive.

Shop for insurance the way you shop for a car

When you decide to buy a car, you think about make, model, year, price, reliability and looks. You think about how much gas it will need and how much repair and insurance costs are on average.

When you’re shopping for a health care plan, you can do your research in the same way. Just like it isn’t only about the car payments, insurance it isn’t just about the premiums. If you anticipate the need for extensive health care services, then a plan with low premiums but a high deductible could end being more costly than a plan with higher premiums but a lower deductible.

Use a navigator

There are a lot of moving parts to consider, and you’re certainly not alone if you feel overwhelmed. One solution is to get help from a health care navigator, an individual or organization that provides free, unbiased ACA Marketplace assistance to consumers, small businesses, and their employees. They can help you determine eligibility, find the right plan, and navigate the enrollment process.

More than just insurance

If you qualify for Medicare or Medicaid, be sure to explore those options as well. In addition to insurance, many employers offer health care savings accounts (HSAs), which allow you to set aside up to a certain amount of pre-tax income for medical needs. Even if your employer doesn’t offer it, you can enroll in an HAS as long as you have a high-deductible health plan (or HDHP). For 2020, the HSA limit is $3,550 for individuals and $7,100 for families.

When you’re seeing the doctor, make sure they listen (and respond) to your concerns. You may not have much choice in care providers during an emergency, but it’s important that you understand the difference between “in network” and “out of network.” A recommended specialist or emergency facility may not have a contract with your primary care provider, which usually means you’ll pay much more than you would for an “in network” provider.

As always, be observant, trust your instincts, and switch primary care providers if you believe you’re getting substandard care due to implicit bias. Since an ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of cure, you’ll want to spend the extra time and energy to find the right primary care provider.

Empower yourself for greater physical and financial health

While we don’t have quick fixes to the problems associated with discrimination, Freedom Debt Relief is dedicated to doing our part to help shed some light and ease the pain. We will continue to provide information about these challenges to help you understand your money, your rights, and ways to better protect yourself and your financial future. Come back to our blogs for additional updates and information with this series and other posts.

Learn More

If You Have Lost Medical Insurance, You’re Not Alone (Freedom Debt Relief)

Racism and discrimination in health care: Providers and patients (Harvard Health Publishing)

What You Should Know About Mortgage Discrimination (Freedom Debt Relief)

Access to Banking: What Does Underbanked Mean? (Freedom Debt Relief)

Debt relief stats and trends

We looked at a sample of data from Freedom Debt Relief of people seeking a debt relief program during May 2025. The data uncovers various trends and statistics about people seeking debt help.

Credit card balances by age group for those seeking debt relief

How do credit card balances vary across different age groups? In May 2025, people seeking debt relief showed the following trends in their open credit card tradelines and average credit card balances:

Ages 18-25: Average balance of $9,117 with a monthly payment of $274

Ages 26-35: Average balance of $12,438 with a monthly payment of $380

Ages 36-50: Average balance of $15,436 with a monthly payment of $431

Ages 51-65: Average balance of $16,159 with a monthly payment of $528

Ages 65+: Average balance of $16,546 with a monthly payment of $498

These figures show that credit card debt can affect anyone, regardless of age. Managing credit card debt can be challenging, whether you're just starting out or nearing retirement.

Personal loan balances – average debt by selected states

Personal loans are one type of installment loans. Generally you borrow at a fixed rate with a fixed monthly payment.

In May 2025, 44% of the debt relief seekers had a personal loan. The average personal loan was $10,718, and the average monthly payment was $362.

Here's a quick look at the top five states by average personal loan balance.

| State | % with personal loan | Avg personal loan balance | Average personal loan original amount | Avg personal loan monthly payment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts | 42% | $14,653 | $21,431 | $474 |

| Connecticut | 44% | $13,546 | $21,163 | $475 |

| New York | 37% | $13,499 | $20,464 | $447 |

| New Hampshire | 49% | $13,206 | $18,625 | $410 |

| Minnesota | 44% | $12,944 | $18,836 | $470 |

Personal loans are an important financial tool. You can use them for debt consolidation. You can also use them to make large purchases, do home improvements, or for other purposes.

Manage Your Finances Better

Understanding your debt situation is crucial. It could be high credit use, many tradelines, or a low FICO score. The right debt relief can help you manage your money. Begin your journey to financial stability by taking the first step.

Show source

Author Information

Written by

Steve Tanner

Steve Tanner is a veteran writer and editor with experience covering topics from law, to business, technology, and finance. He started his career as a business and technology reporter in Silicon Valley and helped lead the direction of several publications, both print and online. His work has been published in Red Herring, San Jose Business Journal, SFGate.com, and FindLaw.com, among others.